Revisiting Sufi Classics

Reading Attar’s The Conference of the Birds

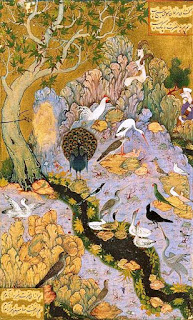

Reading Attar’s The Conference of the BirdsIf one is troubled by the question/crisis of faith, obsessive ritualism, difficulties in understanding the meaning of destiny and evil, guilt and hell, and if one is struggling with religious and secularist fundamentalisms and scores of questions that reason and modernity have raised regarding religion and meaning of life, consider reading Faridudin Attar. Every word of him if one could. Or at least The Conference of the Birds and its superb appropriation by Moore and Corlett in a slim volume Islamic Space that introduces the meaning of Islamic tradition for modern audience in a lucid captivating and arguably irrefutable style. For Attar, as for mystics in general, the question is not of belief/disbelief in some Beyond/God but of exploring the problem of the ego and its resistance to be dissolved by Love. The only doctrine Sufism “teaches” is detachment from/transcendence of all beliefs or positions including the one (ego/I) who seeks belief or disbelief and this brings freedom. Sufism teaches the universal or perennial doctrine of Tawhid or Unity – Non-dualism – which is mistranslated as monotheism by those who know only exoteric theology and as pantheism by those who don’t care to read Sufism properly.

Attar, through the allegory of birds that end their long arduous search for the King (who are mostly consumed in the process or stop short of the goal) by seeing themselves as Kings (this recalls Mundaka Upanisad’s story of two birds living together, each the friend of the other, perch upon the same tree. Of these two, one eats the sweet fruit of the tree, but the other simply looks on without eating. Two birds are, respectively, soul/self/ego and Witnessing Self/Spirit) talks about the odyssey we are called to undertake. To be a human is to be a seeker, to seek to transcend oneself, to move on, to be open to experience, to death and salvation/felicity (to refuse to seek immortality in the mortal world and thus find immortality) lies in sincerity of this seeking or submitting to the other/non-self or experience. In Sufi terms this requires crossing various valleys on the path to the King/Self/Nothingness and let us note that the woe and weal of experience or everything we encounter is an invitation to or manifestation of one of these valleys. Attar shows how to win our salvation with diligence or be light unto ourselves although, he makes clear, that the initiative or the whole drama is ultimately orchestered by the Beloved and wisdom lies in renouncing human wisdom so that one knows God/the Real/Reality by Himself and not by oneself. God pulls us (as Al-Wadood, The All-Loving and as Al-Qahar, The Irresistible Subduer) and our resistance doesn’t count ultimately although it might cost one every kind of humiliation/heartbreak/suffering we encounter in the odyssey of life and then even a stay in purgatory or hell.

Attar is one amongst the seven wonders of Islamic spiritual tradition and his work Mantiqu’t-Tair, as he himself predicted, has stayed for centuries and will stay as long as heaven and earth exist. And “perhaps the sleep which fills your life has deprived you of this discourse; but, having met it, your soul will be awakened by the secret which it reveals.” What Attar told himself: “O you who talk so much, instead of so much talking beat your head and search the secrets.” If we don’t search, the universe or Life beats us in turn to despair. Masters are those who dissolve before the True Master (the Self) and let the latter to speak. It is the Muse that dictates and their job is only to faithfully receive. The proof that this is so is perennial appeal of what they bring forth. Humans are all attuned to certain frequencies from the higher intellectual/spiritual world and can testify to the truth of the inspired Masters as they strike the right chords. We exclaim Ah and sing and can’t afford mere lukewarm appreciation. A great mystic, like a great work of art, proclaims itself and if we fail to be moved, the fault is in us or in “our stars” we have really projected on the heavens. The cherished fruit, fig, might not be digestible to weaker stomach, as Rumi notes, or the splendor of the Sun might disturb those who have problems in the eyes. Great mystic poets have almost everything human soul yearns for – God or Truth dressed in beauty and what else is there to know or enjoy (truth and beauty are one and what else does one need to know as Keats said). Philosophy, religion, art and mysticism are all invitations to a feast that is Life symbolized/evoked by such terms as God/Reality/Self/Consciousness and what if we are offered the essence of every path or something from all the choicest dishes? That is Attar who was a mystic or more precisely a sage who lived as a devout Muslim and produced many great works of art and wisdom.

I will not summarize the story of birds and Simurgh as that should be known by every educated reader. I just choose to note a few statements Attar makes through his characters. Attar invites us to the Being (mystics/traditionalist metaphysicians/philosophers prefer to use the term Being for God as this is more universally and trans-religiously and trans-culturally easily understandable – we all know Being because we are and to be is to participate in the primordial mystery or ground called Being) the recovery of which is the mission of all great poetry and philosophy and religion and mysticism. And he immediately warns against idolatry and rationalism and says that this Being admits of no analogy. “Since neither the prophets nor the heavenly messengers have understood the least particle, they have bowed their foreheads on the dust, saying: ‘We have not known thee as thou must truly be.’” Invitation to gratefully relate to this Mystery of Existence/Life (Yuminoona bil gayyib) is what constitutes the institution of Messengership/Revelation. Attar explains: “To know oneself one must live a hundred lives. But you must know God by Himself and not by you.” Revelation/Intellection let us know God by Himself. And further underscores the point that religious streak in every great “skeptic” who has resisted shallow rationalization of the mystery that confronts us or that is us as Jaspers would say. “No one really knows the essence of the atom – ask whom you will…one is lost in contemplation of such a mystery – it is veil upon veil.” And then what is the key to embrace this mystery and find fulfillment or meaning? Attar answers: “Love is the remedy of all ills, and it is the remedy of the soul in the two worlds.”

The question of theism/atheism appears irrelevant or pointless for a sage as Attar explains: “Whoever is grounded in love renounces faith, religion, and unbelief. Love will open the door of spiritual poverty and poverty will show you the way of unbelief. When there remains neither unbelief nor religion, your body and your soul will disappear; you will then be worthy of mysteries – if you would fathom them, this is the only way." “An old woman offered Bu Ali a piece of gold saying: “Accept this from me.’ He replied: ‘I can accept things only from God.’ The old woman retorted: ‘Where did you learn to see double?..If you weren’t squint-eyed would you see several things at once?” And here is Attar’s comment: “There is neither Ka’aba nor Pagoda. Learn from my mouth the true doctrine – the eternal existence of Being. We must not see anyone other than Him… Whoever isn’t immersed in the Ocean of Unity is not worthy of the race of men. …So long as you are separate, good and evil will arise in you, but when you lose yourself in the sun of the divine essence they will be transcended by love.”

Meeting Khizr is a dream of every seeker but see how Attar understands this encounter: “When you enter into the way of understanding, Khizr will bring you the water of life.” Meeting Khizr requires stopping obsession with the mirror or seeing oneself as the centre. Attar says that God one day said to Moses in secret: “Go and get a word of advice from Satan. ..”Always remember,’ said Iblis, ‘ this simple axiom: never say ‘I’, so that you may never become like me.” “You are as Pharoah to the roots of your hair…Never say the word ‘I’. You, because of your ‘I’s’, are fallen into hundred evils…” Attar, through Hoopoe, asserts, “He who isn’t willing to renounce his life is no man. Life has been given to you so that for an instant you may have a worthy friend.”

Another story (out of scores of them) Attar tells us is that in the time of Moses, there was a dervish who often played with his beautiful long beard while praying. He asked Moses to ask God why he experienced neither spiritual satisfaction nor ecstasy. God answered Moses “Although this dervish has sought union with me, nevertheless he is constantly thinking about his long beard.” On being told this, the dervish began to weap and tear apart his beard. And Gabriel visited Moses again saying “Even now your Sufi is thinking about his beard.” One wonders how widespread is this obsessive attachment for/against what is not God such as beard and hijab today at the cost of union with God. Attachment is the sin. Obsessive reformist attitude is the sin in need of reformation.

A Sufi was stoned by children and as it became dark, hailstones greeted him and he started cursing children whom he imagined were throwing pebbles on him in the dark. But at length he discovered that the pebbles were only hailstones and felt sorry stating: “O God, it was because the house was dark that I have sinned with my tongue.” Attar remarks “If you understand the motives of those who are in darkness, you will, no doubt, forgive them.” Who amongst us has not unresolved grudge against someone and still says “Mlliki yawmiddin” that implies that God alone is the judge.

http://www.greaterkashmir.com/news/opinion/revisiting-sufi-classics/255183.html

Comments

Post a Comment