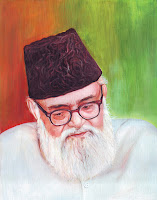

Syed Maududi: A Contested Legacy

Reading Eric Voegelin on Sacred Oriented Politics.

Reading Eric Voegelin on Sacred Oriented Politics.We live in a world where Syed Maududi remains a presence to contend with. One is either for him or against him – there is no option of ignoring him. There remains certain ambivalence with regard to his central ideas amongst mainstream Ulema, and some intellectuals. Ambivalence may be underlined by noting sharply divided estimates of him by Hasan Askari, and his student Saleem Ahmed, two great traditionalist critics of Pakistan. Askari was quite critical of Syed Maududi and a fan of Bhutto, while for Saleem Ahmed converse was true. (Muslim religious/intellectual communities similarly remain divided in their views of revivalist theology and politics). It appears that Maududi would be better understood in relation to the thoughts of the best of his contemporaries in political philosophy and religion. One such illustrious contemporary was Eric Voegelin who shared Maududi’s commitment to the Sacred infused life and public sphere, distrust of secularization project and theological diagnosis of great totalitarian projects that devastated the 20th century, and call for what he called new science of politics whose ultimate objective was to reorient man to the Centre or Absolute.

Syed Maududi’s legacy consists in widespread distrust in secular reason, and polity, in the Muslim world. He has been an indispensable help to reorient many lives towards the Sacred. He has been such a benign influence to new thinking in legal and theological issues to make Islam a living presence and force to reckon with. With faith in both democratic politics and what usually passes for an authoritarian theology, Maududi leads to embarrassing results for both democrats and religious masses. It is little appreciated by both Maududi and his critics that theology, as noted by AKC, is really autology – science of the Self – and God’s rule is the rule of liberated or enlightened self; giving reign to what deserves the rule – Intellect - and this is what has been invoked by philosophers from Plato to Al-Farabi to Aquinas to Voegelin in their own ways. It is also little appreciated that world religions share a principled standpoint concerning politics (there is no such thing as making God irrelevant in public life in any tradition from Hindu to Chinese to Islamic to Judaic/Christian). Maududi, despite some problematic areas in his conceptualization and articulation, has forcefully stated basic premises of this shared doctrine and questioned complicity with reigning secularizing ideology that takes little note of basic objective of politics regarding facilitation for life of spirit – “duty to virtue.” Maududi (and other major figures in revivalist thought), and critics, need to be put in dialogue rather than be allowed to mutually dismiss each other. What is deeply problematic in him is not his basic claim that God has to be given his central place in public life but his insistence that a particular historical period along with the conceptual baggage of later periods have a decisive role in conceptualizing its contours today. Maududi gives little attention to other models of taking note of transcendence in careers of previous prophets, including even prophets in Abrahamic line. Voegelin provides more subtle, more engaging and more careful articulation of the rights of Transcendence and Maududi’s choice to restrict himself to one tradition in a more limiting idiom (theological-legalistic) coupled with less nuanced understanding of complex issues in modernity vis-a-vis transcendence, make for a problematic formulation of extremely urgent or timely thesis that we need to recall in nihilistic times.

Maududi’s reification of Islam into what is dangerously close to an ideology, and an ideology that requires certain political formations for realization, are demonstrably problematic theses that cost him support of traditionally better grounded Ulama fraternity, and more educated modern intellectuals. And this ultimately contributed to decline/stagnation of Jamat-e-Islami, or made it vulnerable to intellectual stagnation. Maududi’s distance from the most important philosophers of the subcontinent (such as Iqbal and Fazlur Rahman), is his distance from the modern intellectual who takes both philosophy and philosophy inflected Sufism seriously. His ambivalent response in mainstream Ulama implies his problematic engagement with the Tradition he inherited, but his critique of fellow Ulama on certain issues can’t be lightly dismissed. Why providence throws up phenomena like Maududi and his critics needs to be appreciated. How destiny has its own logic to unfold is illustrated by the fact that Maududi, one time translator of parts of monumental Asfar-i Arbaea, remained ever suspicious of both philosophy and gnosis centric Sadrean Islamic universe.

Voegelin is one of the very few great philosophers who is well grounded in the sacred Centric Semitic Tradition (where theologians, philosophers, mystics, jurists all have been part of the larger Tradition) and in a position to unearth deeper and essential structures that inform or should inform politics for Revelation centric cultures. He showed convergence between prophetic and Greek approaches, a thesis that has had sizeable following amongst intellectual and spiritual elite of Semitic religions.

Voegelin’s key charges against modernity that it rebelled against God and committed cardinal sin of faith in immanence and earthly heaven have been, independently, made familiar by Maududi and other revivalists like Qutb in the Islamic world. For Voegelin the attempt to cordon off religious beliefs into a purely private sphere when pushed too far by Sacred insensitive secular reason didn’t constitute the West’s unique achievement, but was "symptom of a spiritual crisis unfolding throughout the West."

Maududi’s critique of Communism echoes the Voegelian critique in The Political Religions of totalitarian ideologies as substitutes for religion. However, Voegelin’s The New Science of Politics criticizes as erroneous the idea that God requires (or has given authority to any) puritan army or Gnostic revolutionary to militarily help to bring about millennium-like or heaven-like conditions on earth, an idea echoed in the call to help God be in power politically. Voegelin noted that “there is no passage in the New Testament from which advice for revolutionary political action could be extracted.” This corresponds to the observation made by many critics of Islamic State that the Quran is completely silent on the question of State or revolution or any particular political model of its choice. Far from bringing univocal verses (muhakamat) in their defense, revivalists had to bring verses that required some interpretations to legitimize their project. And this has made their case in principle contestable.

Voegelin has warned against political systematizers and argued that “each society must choose the form of order that is both available and best suited to its reality.” There can be no Standard Model to be mechanically imposed. For Voegelin “the distance between perfection and reality served only to underline the impossibility of their convergence” and we should strive for “a realm of incremental measures” while tempered by “the constant reminder of the threat of far worse outcomes.” Maududi doesn’t appreciate how and why “medieval philosophers, both Jews and Muslims, saw Plato’s ideal republic, ruled by a philosopher and geared to nurture future philosophers, as their model.”

Voegelin was much appreciative of American democracy while Syed Maududi was quite dismissive. It appears that Maududi couldn’t conceive how God had not been dethroned but remained quite relevant in modern institutions despite non-religious (he often took it to be anti-religious) colouring of modern State; for more historical than consciously explicit (anti)religious reasons. He brought theology rather indiscriminately into the realms that theology itself delineated as properly belonging to “non-theological” or purely rational sphere where something like communicative rationality is to be trusted to solve problems.

Maududi posited rather too sharp distinctions between philosophy and theology, between reason and revelation, that Voegelin ultimately deemed passé. Maududi doesn’t seem to have noticed the significance of the fact that constitutions of Modern Welfare States and Caliphate overlap in most of important areas. In practice the absence of the clause that sovereignty belongs to God in modern welfare state doesn’t make much difference in many important spheres where commitment to such values as justice, equality, fraternity, freedom remains enshrined in constitutions. Maududi, like many Muslim scholars, had rather a simplistic understanding of Machiavelli and his context that could be analyzed in light of Voegelin’s reading of him. Maududi didn’t also appreciate danger of turning religion into ideology that has totalitarian tendency. Religion is not an ideology and its addressee remains primarily an individual who is commanded to “strive for righteous rather than perfect community” and for that right order in one’s soul and the soul of the ruler is a prerequisite and in that task philosophers and mystics have a role that Moudidi didn’t fully recognize. The key problem that there is a danger that human interpretation of God’s Word/Law may pose as divinely sanctioned one has been recognized by most modern thinkers.

And it is here that the principle of shura that partly (yes, only partly, pleas of prodemocracy scholars not withstanding) jells with the spirit of modern democracy will have to be properly understood and executed. And if this shura calls the best professionals of various disciplines along with jurists and Ulama for discussions, we would find, presently, little scope of agreement over key issues supposed to represent distinctive essence of Islamic State. We the inheritors of Syed Maududi are required to more carefully think through the problem of interpretation and what constitutes tradition. It is here that likes of Gadamar, modern Judeo-Christian political philosophers, traditionalist metaphysicians and the best of modern secular minds who don’t allow the religious camp any scope for complacency, as Sacks notes, are to be engaged with.

Since the very idea of Islamic State is declared impossible, or unlivable, or unIslamic by many Islamic minds whose commitment to Islam can’t be ignored/doubted. And there is no Church in Islam to legislate against this or that approach. And the standard reproach that they are Westoxicated is unconvincing if we count the evidence of many traditionalist critics of Islamic State idea. The key idea of Syed Maududi regarding urgency to take seriously the call of Transcendence in politics has to be salvaged from ideological colouring. It is in this task that Voegelin would of help and prove ultimately an ally of Syed Maududi.

Comments

Post a Comment